ARTES 25 Years of Telecom: Marking a Milestone

As ESA’s umbrella programme for telecom, ARTES, celebrates its 25th year, we will be examining why it was set up, how it and the European satcom environment have evolved, the opportunities and challenges that both face today, and what the future holds.

As ESA’s umbrella programme for telecom, ARTES, celebrates its 25th year, we will be examining why it was set up, how it and the European satcom environment have evolved, the opportunities and challenges that both face today, and what the future holds.

The early nineties were a transformative time in the European space sector.

The geopolitical scene had changed dramatically in a few short years, with the end of the Cold War in 1991 and the introduction of the EU Single Market making waves across the continent in 1993.

ESA had been keeping an eye on the burgeoning global satellite communications market for a while, and the recent technical and socio-economic developments left it concerned that Europe could be left behind.

By 1993, progress in satellite technology had elevated satellite broadcasting and the distribution of television programmes to an essential presence in people’s homes. Fixed satellite services were enabling high quality telephone connections between different regions of the globe, and the maritime sector was making regular use of satcoms for daily business.

More applications were starting to appear over the horizon too, as digital audio and video broadcasting moved from development to implementation, and ESA projected that satellite’s speed, flexibility and connectivity in areas beyond the reach of ground infrastructure would spark the interest of markets like aviation and terrestrial mobile services.

It was clearly a growth sector, but one that was already being dominated by American companies, helped in a large part by national public investments into research and development as a result of their substantial and well-funded defence programmes.

For example, some of the small platform designs being produced in the US at the time were based on micro-miniaturisation of sensors and electronics that had emerged from the US military programme.

This resulted in American companies having highly competitive small platform designs to offer, without needing to allocate their own resources to testing and validating the products themselves, with similar examples being seen across the satcom value chain; and indeed in other, emerging competitor countries.

Without a pan-European equivalent to this type of support, Europe was financially outgunned on all sides. At the time, Japanese and US total investments into R&D stood respectively at 3% and 2.5% of their gross domestic product, compared to Europe’s paltry 1.5%.

This also led to investment by the private sector in Europe trailing behind the competition, with US companies investing the equivalent of 1.8% of their national GDP and the Japanese private sector contributing 2%, while in Europe, this stood at just 1%.

ESA concluded that without more institutional investment into European satcom R&D, Europe’s industry would miss out on the wealth of opportunity presented by new emerging services and the accelerating deregulation of Europe’s economy, especially in telecommunications.

Earlier, ESA support for individual initiatives in telecom and other space applications had stimulated some useful developments.

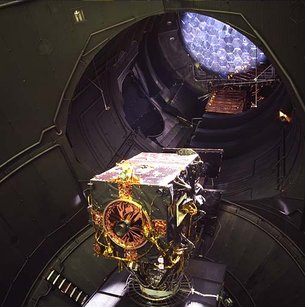

More than thirty satellites could be traced back to technology originally developed by the Agency’s Orbital Test Satellite programme, for example, with the accompanying boost to Ariane launches; and Olympus had birthed a new generation of on-board systems and demonstrated the use of satellite capacity for videoconferencing, distance learning, business broadcasting and VSAT networks, increasing commercial demand in all those areas.

It was clear that corralling all these disparate elements into a broad ESA-led telecom initiative was necessary to enable Europe to compete on the global stage.

So, with the motivation clear, ESA decided on a methodology.

It was determined that above all, ESA’s support should help Europe’s space industry adapt to the ever-changing commercial satcom landscape, as well as provide some counterweight to the advantages enjoyed by European industry’s larger, better supported competitors abroad.

In 1993, it was decided that the best way to do this was to group the existing individual ESA telecom projects under an umbrella programme of Advanced Research in Telecommunication Systems – ARTES.

In addition to the R&D, the programme was launched with the specific objective of helping to de-risk new technologies, with ARTES shouldering some of the financial burden in order to encourage private sector investment in cutting-edge products and services and thereby bring them to market more quickly.

With this, ESA had assumed a role that in other areas of the world was played by the national public sectors. The need for this role would develop even further in the years to come, with the underlying logic still being as relevant today as it was then, but the challenges growing in both scale and number.

Join us in two weeks’ time to find out what this nascent ARTES programme has become, and how the satcom market has evolved in the 25 years since its birth.